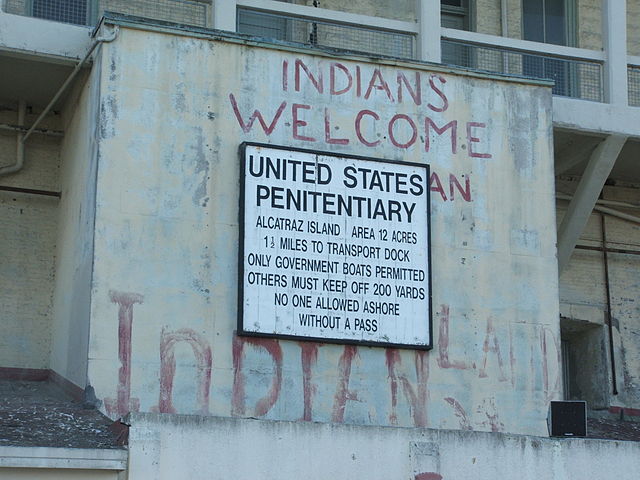

The prospect of a takeover of Alcatraz is likely to conjure images of Ed Harris, Sean Connery and Nic Cage. But 44 years ago from this week, Native American protesters were evicted from the island of Alcatraz after a 19 month occupation. The occupation project began in fits and starts following the closure of Alcatraz penitentiary in 1963. The logic for Native American reclamation of the island came from the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 that stated any abandoned or retired federal land would be handed over to the Native peoples from which it had been taken.

The prospect of a takeover of Alcatraz is likely to conjure images of Ed Harris, Sean Connery and Nic Cage. But 44 years ago from this week, Native American protesters were evicted from the island of Alcatraz after a 19 month occupation. The occupation project began in fits and starts following the closure of Alcatraz penitentiary in 1963. The logic for Native American reclamation of the island came from the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 that stated any abandoned or retired federal land would be handed over to the Native peoples from which it had been taken.

Of course, the United States government had been disregarding its treaties with American indigenous peoples for well over a century. The real impetus for the Indians of All Tribes (IOAT)-organized occupation of Alcatraz was the federal policy of “termination” that had been implemented in the 1940s, which planned to terminate US government relations with tribes, eliminate Native American reservations, close the Bureau of Indian Affairs and culminate in the total assimilation of American indigenous peoples.

President Johnson had proposed ending the termination project in 1968, but failed to do so. When the Alcatraz occupation began in November 1969, the US had been rocked by a half-decade of struggle born from the Civil Rights Movement, which had produced victories to end Jim Crow in the South and make great strides against de facto segregation in other areas of society. Some of the IOAT occupiers of Alcatraz had been organizers in that movement.

At its height, the occupation of Alcatraz counted 400 people, including families with children. Grace Thorpe, the daughter of legendary athlete Jim Torpe (both members of the Sac and Fox tribe), recruited notable figures to support and visit the occupation, such as Jane Fonda, Anthony Quinn, Marlon Brando, Jonathan Winters, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Dick Gregory. Thorpe also procured a water barge, generator and an ambulance service for the island, and Creedance Clearwater Revival gave the occupiers $15,000 (over $90,000 in today’s dollars) that was used to by a boat for reliable transportation to and from the island.

But occupations are eventually undermined by attrition, as we saw with Occupy Wall Street. And, like Occupy Wall Street, the support and morale at Alcatraz was hurt by safety issues and the introduction of street people and drug use on the site. Non-Indians were eventually prohibited from staying overnight on the island to mitigate the disturbances. But in the beginning of 1970, 13 year-old Yvonne Oakes tragically fell to her death, driving her family (who had been key organizers of the occupation) to leave the island.

The Feds cut the island off from electricity in May 1971, and in June a fire broke out and destroyed several buildings. Diminished public support and lack of food and fresh water drove the population of the island down to 15 before a large government force removed the remnant from Alcatraz.

Though the occupation was ended without meeting its key demand (a grant establishing an ambitious Native American cultural center on Alcatraz island, with Native American staff and educators), it is looked upon as turning the tide against the government’s termination project, and after subsequent struggles such as at Wounded Knee, South Dakota (not the massacre), President Nixon put an end to termination, beginning the restoration and establishment of relationships with tribes that exist today.

Video taken at the occupation can be viewed on YouTube, and a documentary on the occupation and its context is embedded below. It is incredible that North American First Peoples took and held Alcatraz Island for over a year and a half. It is even more incredible that the event has disappeared from much of the country’s memory. While we continue to celebrate and draw from the memory of Occupy Wall Street, that occupation is part of a much deeper American tradition from which we can learn.