Just before the appearances of Tarantino and Kevin Smith on the cultural road map and on the radar of film critics and audiences, Richard Linklater had lit up the independent film world with the seminal cult film Slacker.

It was the film that wound up inspiring Tarantino and Smith to just put what they did best on film: talking. Talking about anything.

The general effect of this inspiration by Slacker was that films no longer had to be beholden to the plotting and stale classic structure of Hollywood demands on writers and directors to be formulaic and genre slaves … and that the long-awaited prodigal and revolutionary offspring of the 1970s Hollywood revolution had arrived. The risks taken by directors in the ’70’s was finally showing a manifestation after a strange and weird kind of decade in the ’80’s when all the film studios were, one by one, bought by large corporations and turned into conveyor belts for formula product giving us the worst era in memory (despite smaller indie flashes), the era of Schwarzenegger and Stallone, Steven Seagal and Chuck Norris… buddy cop crap, way too many action films, exploitation of gender and race, what passed more for military propaganda, and the beginning of endless sequels and mediocre cash-ins. The bad guys had won. It was a cultural implosion, but in the middle of that ’80’s period everything appeared to be profitable and moving along perfectly, financially. That was the mood of the ’80’s: Ronnie Reaganism, profits above people, full corporatization, Wall Street picking the bones clean of every bit of meat, cocaine, decadence, superficiality, etc. … sounds familiar again now.

The transition point was short and sort of sudden. 1990 began with a national cultural-consciousness kind of revolution, somewhat out of view at first, beginning with the indie music front that had been there percolating and thriving – and then also the small cult film called Slacker. Slacker reset the barometer and the standards of what films had to do. The rule book had been completely thrown out and now everything was much more free form and optional. Structure, narrative, music, actors, location, script, cost… everything was recalibrated and open to be re-thought. It’s really largely attributable to this one film. Slacker.

But no other film after Slacker was anything like Slacker. Other than the film that Linklater himself made quite a long decade later, Waking Life.

There was something genetically reminiscent about Slacker in Tarantino’s first film Reservoir Dogs and also in Kevin Smith’s first film Clerks: chatty, intellectual, reflecting films. Weird, random, snappy characters who talked about anything and often bullshitted endlessly about American pop culture for no good reason. Or talking about nothing itself. A kind of ironic and defeated celebration of getting back to Point Zero. All the beautiful losers and searchers in one place, in a movie.

What I think is one of the reasons why Linklater is still able to always refresh and appear with new themes and often seeming to make so many films from scratch rather than ever repeating himself like so many other filmmakers is likely because of the artistic foundation from which he emerged – the Generation X slacker culture of Austin, Texas from the ’80’s and early ’90’s. There was an experimentation and a commitment to inventing a new culture in Austin in those years that was staggering, inspiring, and completely socialist, much like Linklater’s defining breakthrough film Slacker, that was a kind of socialist experiment in itself. It was a participation of everyone with actual real life as a backdrop and the place, no better place to be or to get to, as opposed to the equal parts disaffected and superficial 1970’s, and it was the loose and mellow feeling of Austin in those years – the years of liberal culture in Austin and hallucinogenic free thinking of the town and of the forward-thinking elements of UT-Austin had worked. Texas at that time also had a great progressive governor in Ann Richards, Willie Nelson was on his way to being restored as the icon of mellow Texan openness and casual living. And the best band in Texas was the Butthole Surfers. It was all a perfect blend for a film like Slacker to be born. And everyone in Slacker brought some of their own creative mojo to that film. It was how Austin felt at that time and how Austin was.

Drawn to Austin by having seen Slacker and by a friend of mine who lived there, Kim, I sold my whole record collection, other than some rare German Jimi Hendrix albums, in order to move there and made it to Austin by late summer/early fall of ’92. By serendipity I was introduced to the slacker covergirl/ poster girl, Teresa Taylor, aka Teresa Nervosa of the Butthole Surfers, the now legendary psychedelic indie band. She was one of the friendliest people I met in Austin, among many friendly folks, and she said she had a room available in her ranch-house bungalow. I said “Um … YES.”

Linklater’s second film Dazed and Confused had just wrapped principal photography in Austin when I arrived there in 1992 and it would become the film that showed that Linklater was not a fleeting phenomenon, nor was he merely the fortunate beneficiary of the anarchic and mercurially combustible culture of Austin. But there was initially some envy among some of his old friends I talked to about Slacker over the giant success he was already having by then. Some were badly jealous that Linklater had found a way out of the financial privation and subsistence survival of slacker and cafe culture, despite how creatively nurturing all of it was there in Austin. Others had it more in perspective, still knowing full well that Linklater was not turning his back on Austin at all. Linklater to this day has remained in Texas and in the Austin area and has never decided to leap over to the temptations of the Los Angeles cultural wasteland. Linklater had also already back then helped launch the Austin Film Society, which started in 1985 and remains the main purveyor of film culture in Austin to this day.

Whatever the case may have been, besides Linklater’s own motivations, drives, and ethics, one of Linklater’s early accomplices and close friends and a self-styled guru of that creative part of the Austin crowd was Gary Price, with whom I became friends and who taught me a great deal of invaluable things about writing, thinking obliquely, worthy filmmaking, and the craft of creating art as a form of active social and metaphysical evolution, rather than just another career or just another way to accumulate money. The approach was inevitably natural when your mind is freed up… and the approach and maintenance of that state of mind is variably fueled by personal internal ingredients, synchronicity, lots of reading, some alcohol, weed (as needed), uninhibited exploration of all varieties, and letting it all manifest as a sustaining Gonzo manifesto, a living art form, the life as art and not vice versa. Artistic creations then spin off naturally in our wake. This informal and unspoken ontological approach took many of its cues from the Beat generation – Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Burroughs – and also from Bukowski, Henry Miller, and punk rock, and the better parts of the ’70’s film revolution… plus some of the favorite parts of American pop culture to keep it rooted and humble, slightly self-effacing, but not too much, not self-deprecating… but really almost everything in the world outside and even inside of mass-produced culture could be an ingredient. There was everything from cartoons to Tarkovsky to the Butthole Surfers to hamburgers and ribs and then right on back to Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, then bounce back over to all of the American masters of the various arts.

Many artists and filmmakers are consumed by the art itself and often implode. The slacker culture became a power only because it had willingly and intentionally divorced itself from consumer culture and it was also the last generation that expressed itself freely before the hall of mirrors of the perpetually reflecting internet culture, which is now continually burning itself out in the white-light bonfire of digital insanity that now is practically normalized online.

The slacker culture of that former era was a last stand of fending off the hordes of American dream-diseased consumers, the people who had been swimming in mall culture and in TeeVeeLand before the even more soul-draining approach of the Internet and its spawn, social media, etc.

Profits were not a real consideration or motivation for Linklater and the others involved in the production of the seminal indie film. Slacker was financed piecemeal in the pre-digital era by Linklater himself and many other sources and was obviously very low budget, $23,000 total (shot on 35mm). There was a lack of greed and a lack of caring about becoming a “player”, unlike many directors who sabotage themselves cinematically so inadvertently in various manifestations, iterations, and deals that even they start to realize are far too formidably and shamelessly repetitive. And entirely for financial security and artistic guarantees of “the next film”.

Even sometimes at the risk of his own career, Linklater has still been taking on projects and has carried through on ideas that might have seemed to be financially or artistically suicidal to most other directors who see themselves as being pragmatic or realistic… these other directors often are compromising so much in order to get something/anything on the screen. The safe company-man directors’ game plan is safety and maybe sneak an idea or two past the gatekeepers. And also – other directors might have carte blanche and full final cut autonomy and still go with the safe choice, the lack of taking a chance being so built into the process and the pressure that so many directors cannot handle – not wanting to ruffle any feathers or risk losing the comfort of being treated like a god at so many industry events and so on. The “risk” stops being worth it for many successful directors and writers, even long after they’ve earned enough artistic capital to be in a respected enough position to take a few calculated risks. They sometimes insinuate that they respect “other people’s money” too much, in order to defend withering compromises. So product is mostly on the screen in the majority of cinemas around the country and the world, rather than art, more often than not. Safety becomes cowardice.

But that eternal solution: smaller films, no overpaid stars, and budgets that aren’t oppressive. Also, a good script always helps. Werner Herzog also prescribed this recently to counter the corrosive blockbuster effect, but the allure of quick millions at the box office still seems to be dominant – Hollywood is continuing the bigger effects, the dehumanizing CGI, trying to get a superstar to sign, etc., thinking they are responding adequately to the streaming revolution by making films even bigger and more ostentatious, but just signing their own death warrant and delaying disaster for a few more years. Doing the same things they always did.

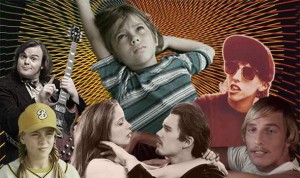

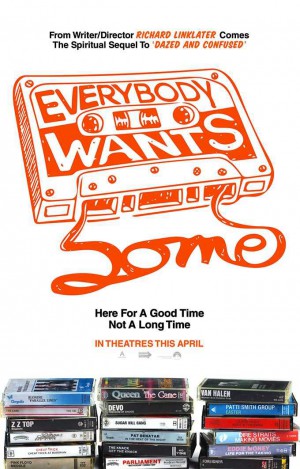

Funny enough, this week Linklater’s latest film Everybody Wants Some is opening the same week that Ben Affleck is in the second week of the quintessential money-draw superhero franchise’s latest Batman face. Affleck got his start and began his career in Linklater’s second film Dazed and Confused, as did Matthew McConaughey. That’s a kind of unifying fact, maybe. Affleck and McConaughey both have in common that they can actually act (most of the time) – and you can give some of that credit to having started in a Linklater film and having that as a steadying part of their roots.

Linklater’s new film Everybody Wants Some is the latest example of Linklater letting his films be a naturally occurring process, not that they aren’t scripted but everyone involved is seen as having a hand in what will eventually be the finished film and it can be seen in the preternatural poise the actors in Linklater’s films often seem to possess. There is actual “acting”, of course, and it is certainly not as spontaneous or as virtuosic as someone like Cassavetes and his films, nor is there much similarity, ultimately, but Linklater does capture an innocence of purpose and a lightness that seems unique to his films and something that was very present in the Cassavetes films also. The absence of the profit motive for both directors is quite likely one of the reasons for this. Art and expression before financial considerations and economic demographic plotting. Any artist worth their salt starts there anyway.

Again, I trace much of this magic and success this to the total commitment to the unspoken socialist and humanist philosophies of the Austin creative community that was the backdrop for Linklater’s early adult formative years, the years where he found an expression, his own voice, a lot of the music he loved, great freaks by the dozens in Austin all committed to knocking over the staid old apple cart of sickeningly mundane conformity, knowing it was slavery long before these themes and beliefs became more commonly held. The freedom was in the self-willed emancipation and the creation of a community that might actually achieve being communal without having to be an entirely separate community, a disavowal. And it’s threaded throughout Slacker, which was the beginning but also a manifesto for Linklater, for the slacker culture all over the country of that era and Slacker has continued to be a film that can be referred back to in order to put into context many of Linklater’s subsequent films and a large part of his philosophy and the Generation X ethos. And when things go awry, watching Slacker is a way to reboot.

From the conversations I had with Gary Price and Teresa Taylor from that time in the early 1990’s, that era was not just an important time in Linklater’s career, of course, but it became the definitions of that time made manifest and solidified and it was crucial. But some of what may have been lost in the sudden success of Slacker was how communal the making of this film really was and from where and from whom it all emerged, of how the monologues in Slacker were mostly if not entirely from the actors’/ participants’ themselves (mostly non-actors were in Slacker, friends of Linklater, Austin residents) and how it was really a group of people who made it successful, not really any one producer or director. But Linklater was indeed the center and the driving force. And the career he forged after Slacker showed that very definitively.

The arc of Linklater’s career has consistently proven to bear fruit, each project often so vastly distinct from previous ones that some film audiences haven’t noticed his signature at times or his brand as a household name, as many audiences are more comfortable with directors who work in similar film genres as they have worked in before or directors of a particular aesthetic, the loud, ego-driven brand-name directors. Linklater has been devoted to taking chances that are not always guaranteed to be successful, but usually are.

Of course, Linklater’s current film Everybody Wants Some is meant to be much like his second successful feature, Dazed and Confused. But clearly this is an intentional book-end, a film about college meant as an accompaniment to Dazed and Confused’s high school theme, time capsules of American life – and Everybody Wants Some was planned quite a few years prior to its completion as this type of film – and it finally hit the screen this week. And you should go see it. Before you go see another brain-shrinkingly shallow superhero movie.

Richard Linklater is among the best American directors working in the film medium today or in any of the past few decades since the 1960’s. And having done that in the largely perilous and shark-infested world of film is really goddamn difficult.